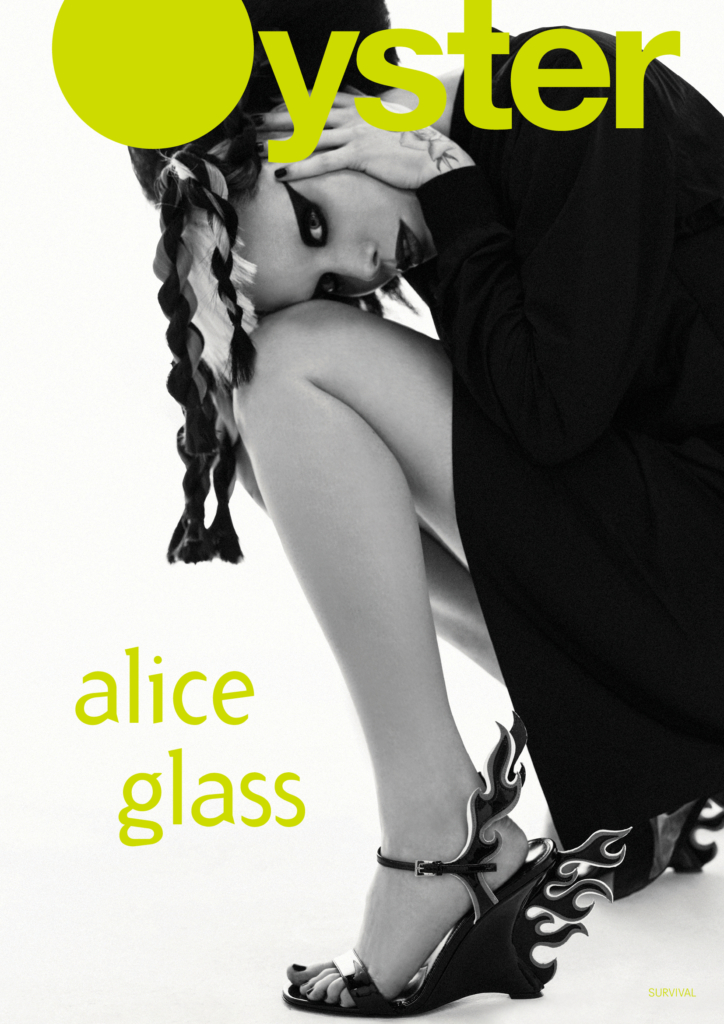

Alice Glass Talks Survival, Recovery And Riot Grrrl for Oyster #115

“Recovery isn’t linear and I think just accepting that is surviving.”

When we first heard from Alice Glass, she was the lead singer of electro-clash outfit Crystal Castles — the no fucks goth princess of our Riot Grrrl dreams. And she still is. But in the years since Crystal Castles, she’s transitioned from stifled collaborator and victim, to survivor and unchained solo artist — with tracks like ‘Stillbirth’ and ‘Mine’ about being violently reborn. And that’s exactly what’s happened. This new Alice Glass didn’t just live through trauma — she overcame it and found her power in the process.

But let’s rewind a little bit: before ‘Mine’, before Crystal Castles, and before the #MeToo revelations about the abuse she suffered from her bandmate, Glass was a shy Catholic school girl who found her way to punk rock through bands like Bratmobile and Bikini Kill. Her influences are part of what always drew me to her. As a teenager, I found myself in songs like ‘Gimme Brains’ and ‘Rebel Girl’, where, for the first time, I realised that girls didn’t have to be quiet — girls could scream, girls could come to the front. And now, more than ever, Glass is the real-life Rebel Girl. When she walks, the revolution’s not just coming, it’s already here.

Alexandra Weiss: Obviously you’ve left Crystal Castles. What has it been like for you to go from working with someone on everything to now working on everything alone?

Alice Glass: Honestly, it was a little intimidating at first. All of the production was always finished before I got there and we never really built any songs together from the beginning. So, there wasn’t ever that level of having to work with any one person and really put yourself out there. Now, I’m working with Jupiter Keyes and some producers that I really love. But sticking yourself in a room with people you don’t know very well can be super intimidating. In the end, though, it’s all the more rewarding to be there from the ground up.

Lyrically, your new music feels a lot more personal. Was it scary for you to put yourself out there, not only on your own for the first time, but in a really vulnerable way?

It’s something I’ve always been afraid to do. But it also just seemed to me that at some point, you have to kind of put your-self out there. I mean, metaphors and imagery are great, but it just wasn’t substantial enough for me to not dig into what I am talking about.

So, in a lot of ways, it’s been like starting over.

It definitely felt like I was learning to write lyrics for the first time.

The theme for this issue is ‘Survival.’ What does that word mean to you?

Just being here and continuing on. Sometimes, simply existing and moving on with your life is a way of fighting back, especially when you’re dealing with trauma.

It’s such a complicated thing, especially in the age of #MeToo, because a lot of people think that to be a survivor means you have to call someone out, or make really visible, overt actions of survival. But I think it can be much more subtle — sometimes, letting go is surviving. But because so many women are putting themselves out there right now, I think a lot of people have forgotten that there’s not only one way to be a survivor…

Exactly. I mean, you don’t have to publicly name names to not be a victim anymore. You can do anything at your own pace because it’s all personal and for yourself. That’s what everyone deserves — to live their life however they choose, as long as they’re not hurting anyone or feeling any remorse. For me, how I’ve been handling things has kind of been really up and down, which I think is the case for a lot of survivors. Some days I feel like I can put a lot of energy into talking to other survivors — which is something I want to be more committed to — but other days, just waking up and being me is enough. Recovery isn’t linear and I think just accepting that in itself is surviving.

Has being creative and working again helped in your recovery?

It’s mixed. When I’m writing, it’s cathartic and I release some emotions that, in many ways, are hard to talk about openly. But it takes a lot for me to finish songs because I always want them to be the best they can be. So, by the time I’ve finished, I’ve opened up all of these wounds — and I guess that’s the point, but it can be draining.

Are there certain things you haven’t wanted to discuss, but have just come out in your songwriting?

On a good day.

So, what’s a bad day?

Sitting, staring at my screen, trying to record my ideas.

When you write about such personal and traumatic events and then you have to perform those songs over and over again — is it triggering? Or healing?

I feel more triggered when I’m sitting in the basement by myself listening to my music. But on stage, I’m just looking at my fans, and how they know the words, and how they’ve embraced my music, and it makes everything seem really real. I mean, I appreciate anyone listening to me so much that it actually made me cry a couple of times on my last tour. Watching people sing along to my lyrics — that makes it seem a lot more real to me than when I’m just writing it.

You said earlier that you don’t think people need to name names or out their abusers in order to be a survivor, but you made a choice to tell your story publicly. Why was that so important to you?

I wanted people to know my story so that I could help en-courage someone else who’s in a bad relationship to get out of it. When you’re in the relationship, you’re so used to how toxic everything is, so sometimes just having someone on the outside say, ‘Wait, this isn’t normal,’ can be groundbreaking.

Has it been easier for you to navigate things as a woman, and as a survivor, in the post-#MeToo industry?

I’m not sure. My label has been really supportive. But honestly, I don’t think anything’s changed in the music industry. Not many women have spoken up yet. And it’s just been years of toxic masculinity and the idea of groupies… So many people are looking back thinking, ‘Oh he was sleeping with tons of teenagers, but I really like his art and I respect him as an artist.’ There’s a line that needs to be drawn but there’s just so many people who are still willing to support bad behaviour as long as it involves the people that keep making money. To be honest, I don’t know if that will ever change.

You bring up something a lot of people are talking about right now: can you separate the art from the artist, especially if that artist is a predator? Does it matter if someone abuses women and makes great art?

No. Definitely not.

I agree, but people are saying things like, ‘I’m choosing to be in Woody Allen’s new movie because who he is as a person is not who he is as an artist.’

That’s total bullshit, and especially with Woody Allen because his movies are predatory and creepy. That speaks to who he is as a person. Fuck anyone who would work with him, and fuck anybody who would work with Roman Polanski. It’s also a pretty privileged problem to have to begin with — whether you should choose to work with a predator or not. So many people out there are trying to figure out how to actually survive and don’t have the resources. But working with someone like that — it’s a huge slap in the face to their victims.

What’s been inspiring you lately?

Whenever I have a eureka moment about things I thought were true — and therefore realise that I was kind of living a lie for years. So, being disillusioned in a way that can be productive is inspiring me right now. I’m still having a lot of moments like that, which is what a lot of my songs are about. Also, Deborah Layton and her book, Seductive Poison. I had to unlearn a lot of false information my abuser had told me to keep me confused and relying on him, and in the first year I was out of that situation, I must have read the book three times. It’s about her escape from Jonestown and how she was able to trust her intuition despite everyone around her telling her otherwise. That’s what helped her survive and it gave me the confidence in my decision to keep moving on and building my own life. Oh, and Tina Turner.

When you were younger, was making music something you always knew you wanted to do?

Growing up, I watched a lot of Much, which was like the Canadian MTV, and I got really into punk rock and Riot Grrrl. I used to lock my door and try to sound like Kathleen Hanna and Allison Wolfe over and over again. Then I started an all-girl band called Fetus Fatale. We only played, like, two shows and got paid in a pitcher of beer. It was pretty messy, but it was the first time I really thought ‘Oh, I could actually do this.’ But I never thought that years later I’d be making a living or being interviewed by an Australian magazine because of songs that I wrote. So, that’s pretty fucking cool.

What was it about punk and Riot Grrrl specifically, that was so attractive to you?

Being a teenage girl was not all rainbows and butterflies — not for me, at least. I had a lot of aggression to get out and punk rock really connected me to it. I started going to a lot of local shows, but there weren’t a lot of female-fronted bands or even girls in the mosh pit. It was a really male-dominated punk scene. Just the amount of old, creepy dudes who thought we were there to sleep with them, or that we weren’t there for the music, or that we couldn’t hold our own in the pit — it just made me angrier and more into Riot Grrrl. Plus, the punk girls in Toronto were always way cooler than the men. I just wanted to stand with them.

What do you think it is about punk that allows you – or at least allowed you at the time — to express yourself as a woman in a way that another genre might not?

When I was thirteen years old, what punk meant to me was calling out the flaws in the system and not getting had, not getting fucked over. Those are pretty relatable themes as a young woman — or as any woman, I guess.

You mentioned Allison Wolfe and Kathleen Hanna — two female artists that have managed to survive in the music industry. Do you have any plans to make sure you can always continue working?

I don’t know, I’ve always been the kind of person who’s just living to finish that next song or that next tour. The most I think into the future is how the record is going to sound. But I’m learning more and getting more comfortable with myself. So, hopefully, that’ll help me.

When I was growing up, I was obsessed with Courtney Love — she was the first girl I’d ever seen who was actually angry. I mean, I was angry, but I didn’t realise I was allowed to be. That was a huge revelation for me.

Totally. That’s what it felt like for me. And in some of the songs, she’s inviting the listener to partake. That was what was so exciting about Riot Grrrl — it didn’t seem closed off. It felt like you could be part of it if you wanted to be.

Do you try to bring that sort of inviting feeling into what you do?

Sometimes, but I’m still a little scared and intimidated by strangers. I definitely want to do that more and I especially want people who have been taken advantage of to feel that they are a part of something too. I just have my guard up a bit.

That’s natural for anyone, but especially someone coming out of an abusive relationship.

Yeah, it’s still hard for me to trust people as I obviously haven’t had the best experiences when I have trusted in the past. But not being able to trust people completely closes you off from life and new relationships and experiences.

Are you angry?

I’m not sure I’ll ever be completely at peace with everything I’ve been through, but being able to express myself — whether it’s my rage, or sadness, or optimism — has been good for me. I think anger can be powerful if you direct it in the right way. Some days, I want to be able to reflect on the past and use my emotions in a way that helps me. But I’d also love to forget everything that happened and stop having nightmares.

Your aesthetic has always been a really big part of your brand. In a lot of your photos, you play both the submissive and the dominant roles. Do you see yourself as one or the other? Or do you think there’s power in both?

Well, I don’t have rules anymore for what I can and can’t wear, and what I can dress like. So, I’m just kind of learning to accept myself, and realize that everything I like is okay — that it’s okay to be me and dress like me. I mean, I’m really into horror movies and spooky stuff, and I don’t care anymore if anyone thinks that’s dorky. So, I definitely think it’s dominant for me to do what I want, no matter what I’m wearing. Even if I’m wearing a babydoll negligee, or tied up, that would still my choice, and that would be empowering.

Do you see your music and your style as an extension of, or as a means to, your feminism, or survival?

In the sense that I can finally do whatever I want, and dress up like whatever I want, absolutely. But I guess clothes have always been a bit of self armour for me. Even now, when I get ready for a show and do my make-up, it’s a bit of a transformation process that makes me feel stronger.

What’s one thing you can’t survive without?

Music.

Making music, or listening to it?

Both, and just being able to connect with it — as an artist and a listener.

interview Alexandra Weiss, photography Georges Antoni @ The Artist Group, creative direction and fashion Charlotte Agnew, hair Sophie Roberts @ The Artist Group using Oribe, make-up Molly Warkentin @ Company 1 using MAC Cosmetics, photography assistants Oliver Begg and Mitch O’Neill, digital operator Jon Calvert, fashion assistant Vicki Liang. Shot at Studio 501, Sydney. Special thanks to Rachel Jones-Williams @ Caroline Australia and Camille Peck @ The Artist Group.